Among the best senses of the human body is the sense of smell or odour. The healthcare process is becoming more intense after the COVID-19 pandemic waves around the world. We are more aware of our senses, which are more affected by people infected with the virus.

The latest research suggests that smells of ripening fruit or fermented foods can cause changes in how genes are expressed inside cells beyond the nose. The findings have led scientists to consider whether sniffing volatile airborne compounds could be a potential treatment for cancer or a way to slow down neurodegenerative disease with further research.

Although delivering medication through the nose is not a novel concept, there is still a notable gap to bridge from conducting experiments on cells, flies, and mice to human trials. Additionally, there may be potential health risks associated with the compounds that have been tested, and therefore, further studies are necessary to gain a better understanding of the long-term effects of this fascinating discovery.

A cell and molecular biologist at the University of California (UC) Riverside and senior author of the study, Anandasankar Ray, stated that, “That exposure to an odorant can directly alter the expression of genes, even in tissues that have no odorant receptors, came as a complete surprise.”

The research team conducted an experiment with fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) and mice, where they were exposed to varying levels of diacetyl vapours for 5 days. Diacetyl is a volatile compound that is usually released by yeast during the fermentation process of fruits. It was previously used to give a buttery-like aroma to food items like popcorn and is also found in some e-cigarettes. Additionally, it is a by-product of brewing.

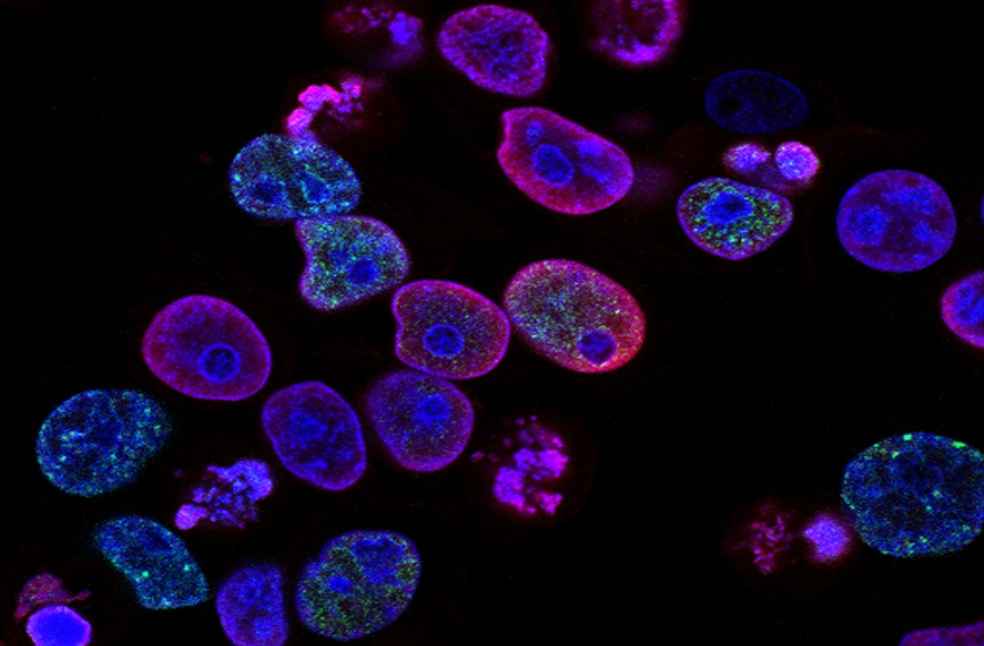

The research team discovered that diacetyl when introduced to lab-grown human cells, can function as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. This led to significant alterations in gene expression in both mice and flies, including changes in the brain cells of the animals, the lungs of the mice, and the antennae of the flies.

HDACs are enzymes that allow wrapping DNA close around histones. When inhibited, genes can be defined more readily. HDAC inhibitors are used as medicines for blood cancer.

In further tests, the scientists discovered that exposure to diacetyl vapours stopped the growth of human neuroblastoma cells in a dish. It also slowed the progression of neurodegeneration in a fly model of Huntington’s disease.

Ray said that, “Our important finding is that some volatile compounds emitted from microbes and food can alter epigenetic states in neurons and other eukaryotic cells. Ours is the first report of common volatiles behaving in this way.”

The team investigated the effects of diacetyl as a proof of concept. However, other research has shown that inhaling diacetyl can cause changes in airway cells and even lead to a lung disease called obliterative bronchiolitis, also known as ‘popcorn lung.’

“This compound may not be the perfect candidate for therapy. We are already working on identifying other volatiles that lead to changes in gene expression,” Ray added.

The researchers noted that, “Given our repeated exposure to particular flavours and fragrances, the findings outlined here highlight a new consideration for evaluating the safety of certain volatile chemicals that can cross the cell membrane.”

Plants contain HDAC enzymes and studies show they respond quickly to airborne volatile chemicals, making agriculture a promising application for this research. The research has been published in the eLife journal.

TRENDING | Cancer survival progress in UK is slowest in 50 years; Study