Cocos (Keeling) Island, West Australia: Scientists have recently returned from surveying gigantic underwater mountains in the Indian Ocean. They saw many deep-sea critters that were adorned with blinking lights, had velvety black skin, and had jaws full of sharp, crystalline fangs.

The team of biologists conducted research in the waters surrounding the Australian territory of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, which are situated more than 600 miles off the coast of Sumatra. Dr. Tim O’Hara of the Museum Victoria Research Institute (MVRI), the expedition’s lead scientist remarked that “It’s just a whole blank canvas.”

The Indian Ocean is rarely visited by research missions, mostly due to its great distance. The journey to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands on board the research vessel Investigator, run by Australia’s national science organization, CSIRO, took the team six days from Darwin in the Northern Territory of Australia.

Strange and Unique creatures in the Deep Sea

The underwater world is home to a variety of species. Here are the few unique creatures found by the Museum victoria researchers under the deep sea of cocos island.

Sloan fish have enormous, fang-like teeth that are visible even with the mouth closed. On its abdomen and top fin are light-producing structures that help it attract prey and ward off predators.

According to Dr. O’Hara, an expert on invertebrates, “The actual stars of the show are the fish. There are blind eels, tripod fish, bubble fish, and dragon fish, all with these bioluminescent organs and bait coming out of their heads. They are just extraordinary.”

A standout among the enormous variety of species they discovered was the deep-sea batfish. It moves around on two small fins that serve as legs and rests like a decorative pancake on the ocean floor. The tiny bait is hidden in a cranny on its nose, perhaps it is an effort to fool victims into believing it’s a juicy worm.

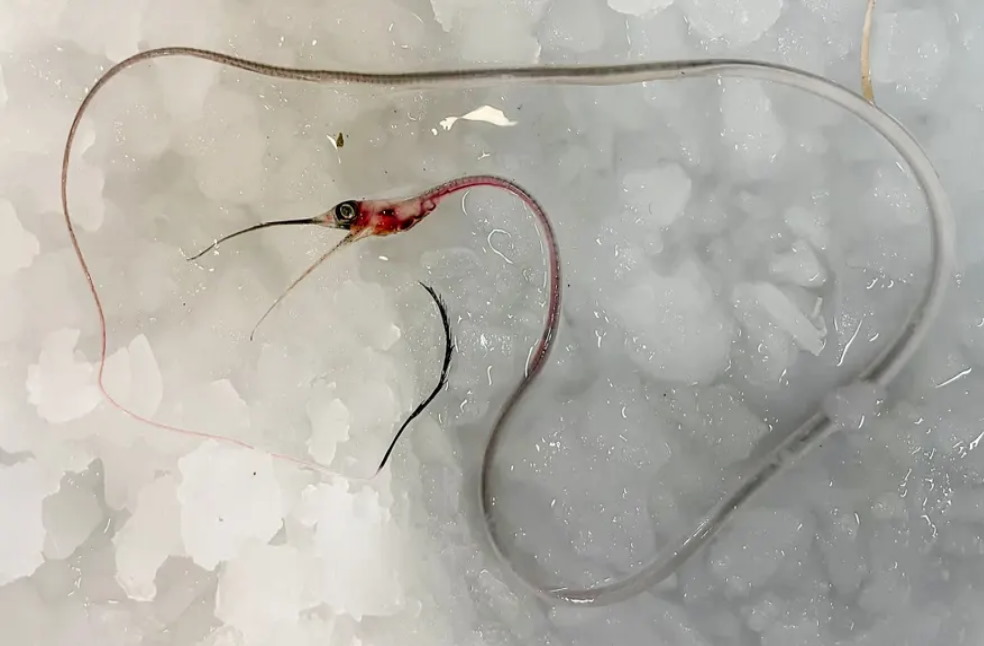

The research team came across a spider fish, which has lengthy lower fins that it uses as a stable foundation for sitting above the ocean floor and for grabbing passing food scraps. They found a previously undiscovered blind snake that was recovered at a depth of 5,000 meters and had skin that was transparent and jelly-like. Researchers discovered loose jaws, a type of dragonfish with an unusual habit of spying on other animals using biological red light, a color that other deep-sea animals cannot detect.

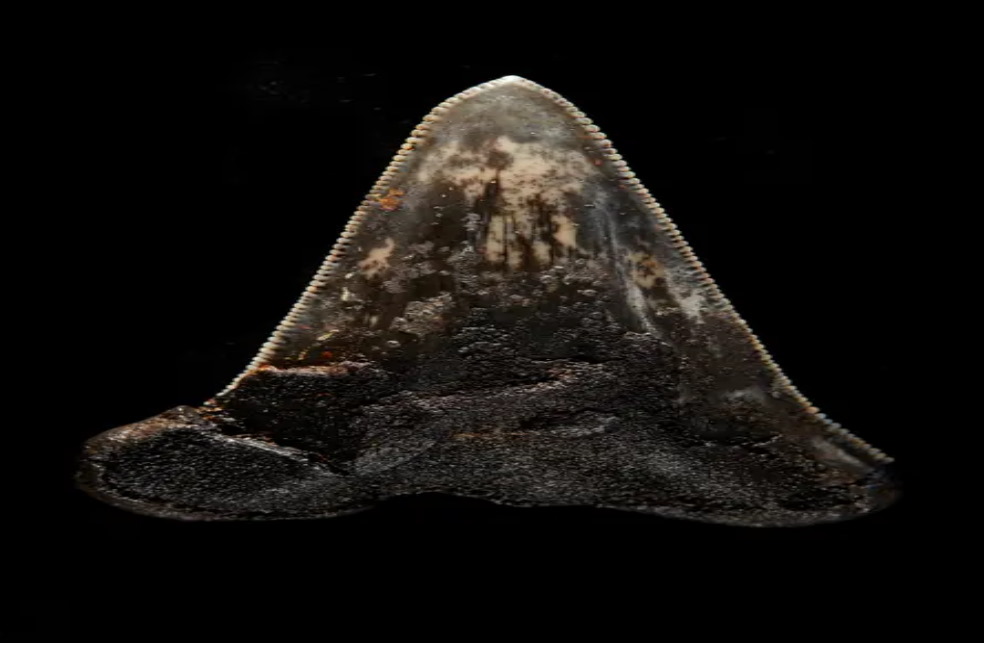

Ancient shark teeth looked to be scattered across a network of samples pulled across the abyssal plain. Paleontologists believe these originated from “megalodon-like animals” based on the photos. More information will become available once they have access to the teeth, which are now being shipped to museums along with the rest of the artifacts.

The researchers not only shed light on deep-sea life in this little-known area, but they also uncovered an intriguing marine environment, featuring enormous underwater volcanoes, or seamounts, that are 5,000 meters tall, more than twice as high as Australia’s highest land mountain.

Using high-resolution sonar to make accurate 3D models of the deep sea floor, the scientists found a lot of smaller seamounts that had never been seen before. Dr. O’Hara predicts that between 10 percent and 30 percent of the specimens acquired by the voyage will be new to science. It will take experts years to go through all the specimens.

The team traveled to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands in order to provide background knowledge to aid in managing and protecting the area’s recently established marine park, which was created in March 2022, along with the nearby Christmas Island Marine Park, which the crew had previously visited.

Dr. Michelle Taylor from the University of Essex and President of the Deep-Sea Biology Society, who wasn’t involved in the expedition pointed out that, “I’m really excited about the new future scientific discoveries that will come out of this in the coming years.”

The team has already decided to compare the DNA from the samples with ecology (or eDNA) DNA extracts sieved from saltwater, which organisms deposit into the mud and skin cells. The hope is that in the future, scientists will only need to look at the genetic traces that the seawater has left behind to identify species located in the deep sea.