Ottawa, Canada: A toddler from Canada is being praised in the science world as the first person to receive in-utero treatment for a genetic condition that would have killed her soon. Ms. Sobia Qureshi, the mother of 16-month-old Baby Ayla, claimed that “She’s our little miracle baby, and she’s shown us that (the treatment) does work.”

Baby Ayla, who lives in Ottawa with her parents Mr. Zahid Bashir and Ms. Sobia, was diagnosed with Pompe syndrome in 2021 and was given an experimental medication while still a fetus. Two of her sisters died from this genetic illness, which is typically fatal. But according to Baby Ayla’s family and doctors, she is not only surviving but also doing well. This was written in a report in the New England Journal of Medicine, which called her case the first time anyone tried to treat the condition while she was still in the womb.

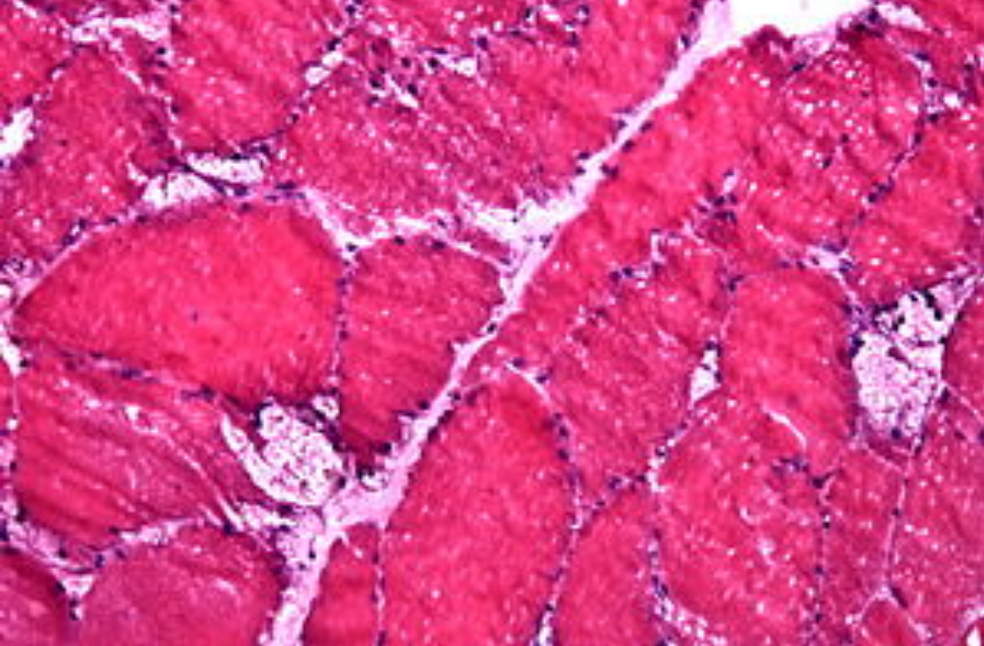

Baby Ayla, who is 16 months old, has infantile-onset Pompe syndrome, a genetic condition that can result in organ damage that starts even before birth. A baby with Pompe has a larger heart and weaker muscles at birth. If left untreated, most infants die before reaching the age of two. However, this approach does not stop the permanent and potentially fatal organ damage that occurs in utero. Instead, treatment often starts after birth.

As part of a clinical trial that was in its early stages, Baby Ayla got treatment while still in the womb. The toddler is currently completing developmental milestones, including walking, and has a healthy heart. A study that came out on November 9 in the New England Journal of Medicine says that her success shows that the condition can be treated during pregnancy to stop organ damage and lengthen the lives of unborn children.

Dr. ill Peranteau, a pediatric and fetal surgeon at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia who wasn’t involved in the work claimed that “It’s a great step forward.”

Less than 1 in every 138,000 newborns born worldwide suffers from infantile-onset Pompe disease, an uncommon disorder. It is brought on by genetic alterations that either lower levels of the acid alpha-glucosidase (GAA) enzyme or stop the body from producing it at all.

GAA converts the complex sugar glycogen into glucose, the body’s primary energy source, inside cellular organelles known as lysosomes. Glycogen builds up to dangerously high amounts without GAA, which can harm muscular tissue, including the heart and the muscles that aid in breathing.

Baby Ayla was diagnosed with the most severe form of Pompe disease, while other people can develop it later in life or have a less severe version that doesn’t enlarge the heart. She doesn’t produce any GAA in her body. If treatment begins soon after birth, replacing the missing enzyme with an infusion can help prevent glycogen accumulation.

Early research in mice revealed that prevention of a Pompe-like disease may be accomplished by medication. So pediatric geneticist Dr. Jennifer L. Cohen of Duke University School of Medicine and colleagues began a preliminary clinical trial involving Pompe and seven other lysosomal storage diseases that are comparable to Pompe.

When her mother was 24 weeks pregnant, the team began treating on Baby Ayla by injecting GAA through the umbilical vein. Six injections were given to her mother, one every two weeks. Since she was born, Baby Ayla has been getting weekly infusions, and the medical staff will keep doing this for the rest of her life.

Dr. Cohen claims that the therapy was risk-free for both mother and child. But it’s not known whether this prenatal enzyme replacement is always a safe and beneficial alternative until more people are treated and evaluated in the experiment. The trial has treated two additional patients with different lysosomal storage diseases thus far, but it is too early to tell how they are doing.

According to Dr. Cohen, it is currently unknown how Ayla and other patients who have received treatment will fare over time. Dr. Cohen pointed out that “We’re cautiously optimistic, but we’ll be cautious and monitor the patient for the rest of his or her life. Especially those first five years, I think, are going to be critical to see how she does.”