Pennsylvania, US: According to a groundbreaking study on brain plasticity and visual perception, individuals who had surgery as children to remove half of their brains consistently detected differences between words or faces more than 80 percent of the time.

Given the size of the removed brain tissue, the unexpected accuracy emphasizes the brain’s ability to adapt to traumatic injury or dramatic surgery as well as its limitations in doing so.

The results, which were presented recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, represent the first-ever attempt to define neuroplasticity in humans and determine whether one brain hemisphere can carry out tasks that are typically performed by the two halves of the brain.

The question of whether the brain is prewired with its functional capabilities from birth or if it dynamically organizes its function as it matures and experiences the environment drives much of vision science and neurobiology. Working with hemispherectomy patients allowed us to study the upper bounds of the functional capacity of a single brain hemisphere. With the results from this study, we now have a foot in the door of human neuroplasticity and can finally begin examining the capabilities of brain reorganization

Prof. Marlene Behrmann .

In response to changes in its environment, the brain can alter its activity and rewire itself, either physically or functionally, due to a process called neuroplasticity. Our brains continue to adapt well into adulthood even if brain plasticity peaks early in development.

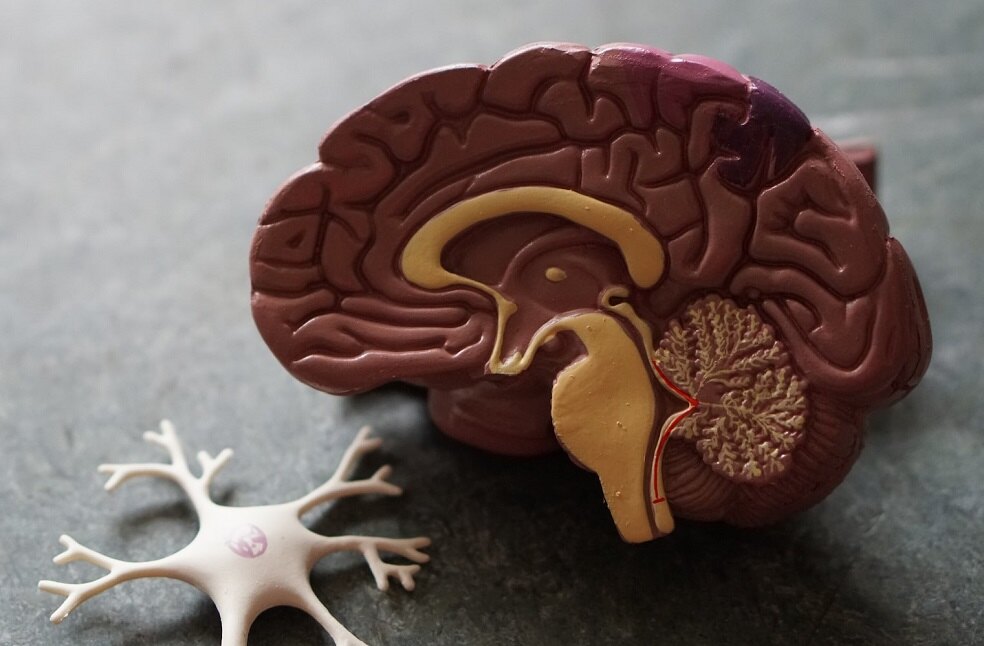

The two parts of the human brain, known as the hemispheres, are specialized more and more as we mature. The left hemisphere develops into the primary location for reading printed words, whereas the right hemisphere develops into the primary location for recognizing faces, despite the fact that this division of work is not absolute.

However, neuroplasticity has its limits, and throughout time, this hemisphere preference becomes increasingly fixed. Adults who encounter a brain lesion due to a stroke or tumor may occasionally lose their ability to read or acquire face blindness, depending on whether the left or right hemisphere of the brain is affected.

To understand what occurs when the brain is forced to evolve and adapt when it is still extremely malleable, researchers examined a specific group of patients who had undergone a complete hemispherectomy or surgical removal of one hemisphere to control epileptic seizures during childhood.

Scientists rarely get access to more than a few patients at a time due to the relative rarity of hemispherectomies. COVID-19 did, however, have one unexpected upside for the Pitt team, it allowed for the normalization of telemedicine services, which allowed for the enrollment of 40 hemispherectomy patients, a record amount for trials of this nature.

Researchers gave participants pairs of words, such as “soap” and “soup” or “tank” and “tack,” each changing by only one letter, to test their ability to recognize words. Scientists presented pairs of photographs of people to the kids to see how well they could distinguish between different faces. The participants had to identify whether a set of words or a pair of faces were the same or different after only a brief glimpse of either stimulus on the screen.

Remarkably, both of those functions were supported by the lone remaining hemisphere. The ability to recognize words and faces varied between control patients and those who had hemispherectomies, although the changes were minimal and the average accuracy was greater than 80 percent.

Patients’ accuracy on word and facial recognition was comparable when matching hemispheres from patients and controls were directly compared, regardless of which hemisphere was removed.

“Reassuringly, losing half of the brain does not equate to losing half of its functionality. While we can’t definitively predict how any given child might be affected by a hemispherectomy, the performance that we see in these patients is encouraging. The more we can understand plasticity after surgery, the more information, and perhaps added comfort, we can provide to parents who are making difficult decisions about their child’s treatment plan,” stated Michael Granovetter, a research student in the Medical Scientist Training Program at Pitt’s School of Medicine.